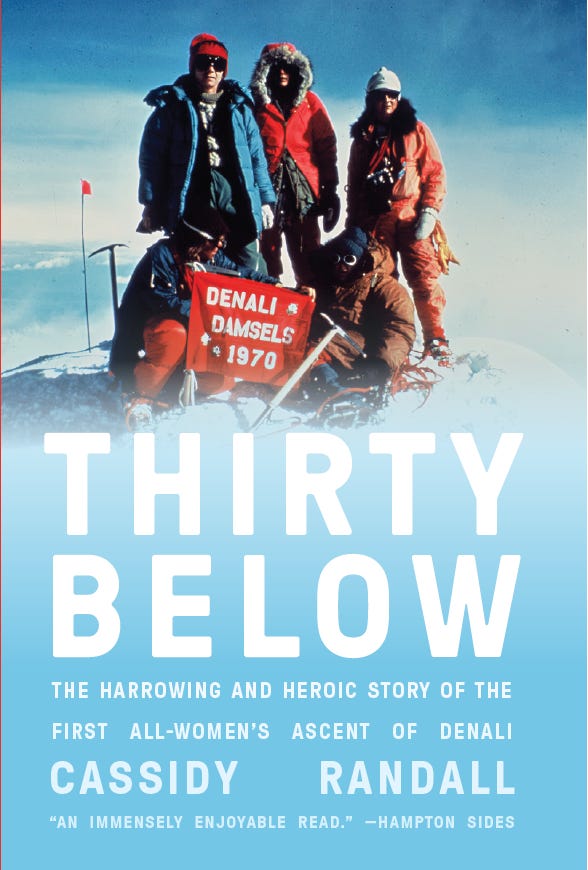

In July of 1970, six women stood atop of Denali in Alaska. They were the first all-women’s team to summit the tallest peak in North America, the first-all women’s ascent of any of the world’s biggest mountains.

It was audacious, this belief that women could climb and survive the extreme elements at high altitude. But Grace Hoeman, Arlene Blum, Margaret Clark, Faye Kerr, Dana Isherwood, and Margaret Young battled misogynistic and sexist beliefs about women’s capabilities just to get to the start of the climb. They each had their own individual reasons for why they wanted—and needed—to succeed. And they knew that their success, or failure, would be an harbinger for all women.

Their story is the subject of Cassidy Randall’s new book, THIRTY BELOW1, which published earlier this month. Cassidy writes beautifully about adventure and the outdoors (you have to read this Atavist story about Susie Goodall and her attempt to sail around the world in her sailboat).

It’s surprising—or maybe it’s not—that their expedition didn’t make headlines and isn’t more widely known because this story is full of all the drama and tension and danger—disaster strikes at the worst possible moment and the team has to figure out what to do and how to survive—that we often look for in a good adventure story.

We share the same agent, which is how we initially met, when Cassidy was just getting started on THIRTY BELOW. I knew that I wanted to hear more from her once the book was out. I’m fascinated by what drives people to climb big mountains (because I am a scaredy cat), especially when there are so many forces working against you. How do you persist? And why?

Cassidy graciously agreed to chat with me about the book and her writing process. What follows is a lightly edited version of our conversation. I hope you enjoy it.

Christine

Can you introduce yourself and what you write about?

Cassidy

My name is Cassidy Randall, and I love to write about adventure and the environment and people doing extraordinary things. This latest book is the culmination of all of those things. And it was really fun to write,

Christine

I want to start by painting a picture of Denali, especially for folks who aren't familiar. What makes Denali so unique, so challenging?

Cassidy

People might know Denali because our president decided to rename it, although climbers and Alaskans have come forward saying they will never call it anything but Denali. But people probably know that it's the highest peak on the North American continent.

While it's not the tallest mountain in the world, it's one of the biggest. It’s sort of notorious as one of the most difficult mountains to climb. Not necessarily because it's the most technical, but because it sits on this plateau at 2000 feet, which means that it rises 18,000 feet from its base to its summit, which is 6000 more feet than Everest rises from its base. That immense elevation gain requires climbers to be on the mountain for longer to acclimate as the oxygen recedes from the air.

What that means is that they're exposed to these wildly fierce weather patterns that hit Denali, because Denali is the highest polar mountain. Where it sits close to the coast, it gets these just like quicksilver fast, bitingly cold storms out of nowhere. And even today, the weather is really hard to predict there. I have had friends who are accomplished mountaineers who have been on Denali and said that it was the most intense experience they've ever lived through. It's constantly freezing and it's constantly just huge winds in excess of 70 miles an hour. It’s a really unforgiving place.

Christine

What was climbing it like in the 1960s and 1970s?

Cassidy

Let's remember, a lot of people have climbed Denali now, but at that point in 1970 it hadn't been climbed all that much. And context is important here—by 1970, we had sent men to the moon and women hadn't stood on the highest peaks on Earth, which is wild to think about.

There was this popular narrative held that women weren't strong enough to withstand climbing mountains, emotionally and physically. Part of the physical part was the way that mountains were being climbed then, which was called siege style.

You were carrying so much food and gear up to establish a succession of camps up the mountain, so then they would all be fully stocked. You would put all of this gear on your back, and the gear then is so heavy. I mean, these frame packs, they're insanely heavy. The snow shoes were these monstrosities that were three feet long, made of wood.

It’s really different from the light-and-fast style of climbing of today. It was like you were hoofing it up and going back to camp Getting the next load and then back again, like you were piggybacking your way up. You weren't just climbing Denali once. You were probably climbing it like two or three times.

Christine

You just mentioned that there are all these ideas about women and what they can or cannot do, and it's it's interesting, but not surprising, that there aren't that many women at the center of these types of adventure narratives.

How did you come across this story? What struck you about it and why did you want to dig into it and write about it?

Cassidy

We both have the same fantastic agent who has an almost magical capability of finding a good story and championing it, and so I definitely have to give her credit for the origin of this one. It was like one dark February day in Montana, and she sent me this email and all it had was a link and one line that said, “Is there a good story here?”

The link was to this National Park Service blog post from a few years before that was celebrating this all-women's ascent of Denali. It was maybe 500 words. Really short.

I had been writing about adventure, and specifically women's issues in adventure, for years by then. I'm really well steeped in the mountain world, and I never heard of this. It seemed like something that should be in our historical consciousness, the way that it is that Lynn Hill freed the Nose in the 90s in Yosemite, yet it's not so why?

Even just in the initial research of digging to see if there was enough here to tell a story, what came out about these women is that they were so complex, and they all had these very different stakes for why they wanted to do something like this, which was no small undertaking. It wasn't just the fact that it was a really hard climb. They were trying to do something that literally everyone thought was impossible, even they didn't know if it was possible for women to do this on their own.

That really drew me in because I think that we still live in this era, even today, and especially back then, where women were only allowed to play the roles that had been historically assigned to us. It's like lone heroin, damsel in distress, princess, witch. We're either canonized for being likable or we’re villainized for being unlikable.

And what I loved the more I learned about these women is that they all were on their own, totally different arcs of development. It was really amazing to be able to get in their heads and be able to tell that story.

Christine

I want to get to how you got into their heads to tell their story, but just going back for a moment. You were saying that women really just weren't allowed in so many of these realms so this idea of this all-women expedition took on so much more meaning. You could tell through your storytelling, too, how much pressure must have been on them. To feel like they had to succeed. That they couldn't accept any help.

Can you talk a little bit about that? That dynamic of not only are we doing this, but we need to to prove ourselves in terms of how we were doing it?

Cassidy

I think we all know this to a certain extent—but writing the story really hit it home for me—that boundary breakers, no matter who they are, by default, they don't just represent their own capability. They're representing the capability of an entire peoples or demographic that they come from.

So these women, they knew that they were representing all women on this climb. It’s very clear, they knew that from the letters between Grace Hoeman and Arlene Blum—Grace led the climb and Arlene was the deputy leader. And they knew that if they failed, it was going to be blown up. They knew that they were going to be subjected to heightened scrutiny.

And that kind of pressure? Holy moly. It wasn't just the failure. It was all these digs like, it's an all women's team so cat fights are going to break it down. So Arlene feels this pressure to keep harmony, to make sure they're all friends at the end of it, which is such a thing that only women are subject to, right? So there's that huge pressure.

Then there were these individual, personal pressures in addition to all the cultural stuff. Grace had been turned back on Denali twice. In her writing, she talks about, if I don't make the summit on the next try, the park will never let me climb it again. I won't be invited on these expeditions to the Himalaya. There were huge stakes for her. Arlene had been told no so many times that she just wanted to prove that it was possible, that women could do this.

Then you had a totally 180-degrees stakes where you have Margaret Clark, the New Zealand climber on the ascent, who had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis a few months before the ascent. You couldn't write this as fiction. She knew that this was potentially one of her last tries at a big mountain expedition before her body just gives up on her.

All of these differing pressures, in addition to the pressure they all were under, and then you put them and the harsh elements of a high altitude, stormy mountain, like, my god.

Christine

They knew that if they failed, it would be blown up. It would be all over the headlines, proving the point that women can't do it. And yet they succeeded, and it wasn't anywhere in the headlines.

That was the interesting part. You talked about the timing of this ascent, how it happened just a few months before the birth of second wave feminism. It made me think, if their expedition happened a few months later, how would that have changed things?

Cassidy

Bay Area papers covered their climb. Some anchorage papers cover the climb. Margaret wrote about it in Christchurch.

But no national newspapers covered this success. This is me speculating but also based on my own lived experience, but I think that's because culturally, we are so much more prone to propping up whatever narrative serves the dominant narrative, which, in this case is that women can't do this. Stories of failure tend to be much more played out than success stories.

What I also think backs that up is that there's this amazing moment two years after the Denali climb. Arlene is reading the Los Angeles Times, a major national newspaper, and there’s a story about supposedly the first all female ascent of Denali. It was this team of Japanese women the paper talked about the fact that three of the women died on the climb.

What it did not cover, and I had to go back and find this information, was that the team summited and there were two survivors. It was a five woman team, and yet, all it is is that these women were found dead on Denali.

Christine

That's wild. It makes you think about how do we record history? What stories are we actually writing down in the records versus the ones that aren't recorded and are potentially lost.

Cassidy

Exactly.

Christine

We started talking a little bit about some of the barriers these women faced climbing these high peaks. The piece I found most interesting were all these beliefs about what women's bodies can and cannot do. Their limitations. Can you talk to me a little bit about that?

Cassidy

Yes, because I was talking to you about it as I was writing.

Christine

And I’m pretty sure I said something like, I don't know! I don't think there's any research on this.

Cassidy

There's no research. That's the crazy part. This is before Roe v. Wade. The birth control pill has only just been introduced and it's really expensive. This is pretty soon after Betty Friedan wrote The Feminine Mystique. So it's definitely in the infancy of this idea that women can be anything except mothers, right?

There are these ideas that if women run marathons, their uterus might just fall right out of their bodies or they would develop mustaches or they’ll get really big and ugly. It’s all just ridiculous.

What you and I talked about is this idea that people thought that women's periods made them weaker and prone to hysteria on a monthly basis. I wrote this in the book because I really loved this idea. Imagine that a woman on her period—who is navigating hormonal roller coasters and is in pain—can achieve the same summit that a man can. Or anything, right? Run a marathon, whatever it is.

This idea that she can achieve the same summit as men while in such a state as some people can be on their periods. What a powerful threat to the foundations of that narrative.

Christine

It's such a blow to the ego in terms of this whole idea that the women are weaker, yet they’re navigating so much more than the men while doing the same thing.

Cassidy

Margaret Young, who was on the team and is a fascinating person, her son told me she was getting her PhD in physics at MIT at a time when there were no women doing that. She gave birth at home and she went back to school the next day, which is another blow to the idea of women as the weaker sex.

Christine

You also wrote about how the women participated in a scientific study at the University of Alaska at Fairbanks, being evaluated before and after the expedition. Did anything ever come of that? Did they publish that research?

Cassidy

I could not, for the life of me, find that published research. I think it’s because the army was conducting the research because mountaineers were the easiest people to study how bodies reacted in altitude and really harsh conditions. But even a Freedom of Information Act requests turned up nothing. So if that study exists, it never made it to the light of day.

But you almost think, well, who cares? Because they proved that their bodies were just as capable.

Right before their expedition, Arlene got this backhanded compliment—this guy was really trying to be conciliatory and supportive. He was like, women should be able to climb Denali more readily than men. They have all that extra insulation. It makes you wonder, like, well, I don't know, what does extra body fat help you? Who knows?

Christine

I want to talk a little bit about how you reported this. How were you able to piece together this story since there aren't many records? Who did you talk to? Was hard to get buy in from folks to to tell this story?

Cassidy

I reached out to Arlene right away and essentially asked her blessing. I actually knew her from my previous life as an environmental health activist. Arlene is a chemist and I had no idea she was a mountaineer. It's funny because she doesn't think that the Denali ascent was that big of an accomplishment. She's also so steeped in that mountaineering world and has done so much since then.

She told me that all of her records are archived at Stanford University. I knew from my early research that Grace Hoeman’s life was archived at the University of Alaska in Anchorage. Before I even got up there, I had read that there was this really compelling and heartbreaking love story between her and her husband, and so I couldn't wait to get up there and see what was there. There were so many letters, not just to do with the Denali climb but her early life too. Grace’s daughter is alive and lives outside Anchorage. I got some time with her, too.

Between Grace’s and Arlene's archives, there’s this library of correspondence between all the members of the climb. It's this amazing timeline of how they planned it, and you can see them becoming friends over all this correspondence.

There are four surviving journals from expedition members. These are not your typical mountaineering journals, which are often just weather or routes or stats. These are like internal journeys, just incredible writing. Then I talked to so many people who knew the women who had died.

As I was finishing up this research and getting really into it, I was like, this was the first all women's ascent of anything so I did a lot of reading to back that up to make sure that was true.

Christine

What struck you most about the story and the women? Are there specific scenes or characters that stick out in your mind?

Cassidy

I love the way that Grace, who leads the climb, changes so much over the course of the book. At the beginning, you're rooting for her, and you have so much sympathy for her and empathy. By the end, you almost want to strangle her.

It was so important to me to write who these women were and what stakes they were carrying and what their motivations were, so you understand why Grace changes the way she does and why she might have made these decisions that you are so frustrated with.

What I didn't put in the book was this vitriol between Grace and Arlene and the aftermath. There were these letters and they are so mean to each other. I didn't put it in because it didn't seem to serve the narrative, and it seemed to only prop up the cat fight trope they’d been trying so hard to avoid. But I remember when I stumbled upon those letters in Arlene's archives, I don't if disturbed is the right word, but it just was like, oh.

It led into one of my big takeaways that I have at the end of the book, how we expect the heroes in our stories to be on this typical hero's journey. Part of that hero's journey is that they all return from whatever quest lifelong friends. That's so ingrained in our cultural storytelling that when it doesn't happen, it upsets you.

I think part of that is because we also expect our heroes to have everything figured out. That's why they're our heroes because they figured out everything with which we're still struggling. It took me a while to come to that, but that, for me, was a really interesting revelation.

Christine

I was curious about what those relationships looked like at the end of all this because by the end of the book, I was very mad at Grace!

Was there anything else that surprised you or wasn't quite what you expected?

Cassidy

I was floored to learn that Grace had been on the mountain during what is still, to this day, considered the greatest tragedy ever on Denali.

The book opens in 1967 on Grace's first expedition to Denali and she's turned back halfway. Grace was on the mountain for it when the storm breaks over the peak, and winds are estimated to be 300 miles an hour, and seven men die at the top of it. She knew what the mountain was capable of, and went back anyway. I can't even imagine.

Christine

As we said in the beginning, there really aren't that many narratives that center women and women's experience. We're getting more now, but especially in the adventure space, the mountaineering space. Why are stories like this important? Why do we need them?

Cassidy

I love that question. We need role models to show us what's actually possible. I think we need it now more than ever because we're in this period of increasingly permissible misogyny and backsliding of women's rights. We need these stories of female mettle and bravery and curiosity and impact right to know what we're capable of. We need stories like this, for women and girls to see themselves in these real-life historical adventures. And we need men to see the possibility of heroic women.

I've been thinking about that a lot, and I think that there's so many more stories like this out there that maybe you're just waiting for the one that opens the floodgates for the rest.

Thanks to Cassidy for sharing a behind-the-scenes look at her new book, THIRTY BELOW.

Links & Things

This post also makes me want to turn off my phone but like forever. “Who benefits from my exhaustion? Not me. Not you. Not the people we love. But the people in power? The ones profiting from our exhaustion? They’re thriving.”

Do you weigh yourself? I have a complex relationship with the scale and don’t have one in the house. This post brought up a lot of feelings—that no matter how much I’ve worked on how I think about and perceive body size and weight, those numbers still have a way of infiltrating past all of it and how I feel badly about that. And also how we can so vehemently fight against perceived change in our bodies, and how our ability to resist change, whether in weight or aging is somehow linked to our value and self-worth. So many thoughts on this.

Mothers and daughters, amirite?

Book I am currently obsessed with.

This is an affiliate link to Bookshop.org. When you purchase something, I may receive a small commission and you’ll be able to support an indie bookstore of your choosing.

Great interview, and I'll definitely read her book! I see parallels between it and one of my favorite books from last year, "Brave the Wild River" by Melissa Sevigny, about two women scientists in 1938 who rafted the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon. The sensationalistic, sexist coverage of their expedition focused on their likelihood of failure and potential "cat fights," ignoring their scientific purpose.