Something new! You may notice that this newsletter is coming from a new address. It also has a new name. I decided to move over to Substack because it offers some more flexibility and features that Tiny Letter just didn’t have. I know that some of you have been with me since my old blogging days—thanks for sticking with me. For those who are newer around here, thanks for coming along this journey with me.

They say that injuries are more likely to happen on the last run of the day. It makes sense. After a full day of skiing, your quads and calves are wiped. Your brain too, probably thinking about that après ski drink waiting for you at the lodge. So you make a little mistake, like a sloppy turn, and you end up on your backside or worse, a total yard sale down the mountain.

It wasn’t supposed to happen on the second run of the day, on a run covered in knee-high, fluffy, buttery powder.

And yet.

I knew the minute it happened. Actually, I heard it. I felt it.

I came off a turn, caught the tiniest bit of air, and landed. Hard. The ground wasn’t where I thought it would be and I ended up stomping straight down on my skis. I can almost see it in my mind’s eye—my lower leg and femur coming together like a crumpling accordion, driving all that pressure and force into my left knee. It was too much for my joint to absorb and something had to give. That something was a ligament popping like a balloon when squeezed too tightly.

I sat back in the snow. I couldn’t move. I couldn’t imagine bearing weight on my leg let alone ski the rest of the way down. I had no choice but to wait for ski patrol to come and get me.

They wrapped me up like a burrito and dragged the sled through back trails to the base of the mountain. Snowflakes rained down on me, coating my goggles until everything was a hazy grey. At times the snow was higher than the lip of the sled I was riding in.

I was so mad—at myself for getting too excited about skiing in Lake Tahoe (one of my favorite places and a place I don’t get to visit often since I live on the east coast), for hurting my “good” knee—and so frustrated—at my bad luck, at my body, at missing this epic ski day.

This wasn’t my first encounter with injury.

I tore my ACL and meniscus in my right knee skiing in college. (My first run-in with ski patrol.) I dislocated my shoulder training for an Olympic-distance triathlon while—get this—swimming. (I know. I know! Who does that?) I re-tore my ACL 15 years later while training for a half marathon. I wore down my rotator cuff in my shoulder from overuse. I re-tore my meniscus skiing four years ago. That’s not even counting the bouts of plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendonitis, IT band syndrome, and achy hips.

Added up, that’s two knee surgeries, one shoulder surgery, and countless hours in physical therapy. Now, there’s the prospect of a third knee surgery on the horizon.

Every time there’s a new injury, I’m asked, “Why are you always injured?” My mom not so subtly suggests that maybe it’s time that I stop running or lifting or skiing or insert-activity-here. Maybe it was too much for my body to handle.

But the thing is? I love being active, even though I’m not the best or most talented athlete. There’s something about moving my body that makes me feel most like me.

What’s an Injury-Prone Body?

Our culture loves to celebrate athletic achievements, especially if it involves overcoming a challenge in order to succeed. Just look at the coverage during the Olympics. Sprinkled between the various sporting events are human-interest stories, about the parents who sacrificed so their kid could compete or how an athlete fought back from a potentially career-ending injury to achieve their Olympic dreams. It’s inspiring and encouraging, that can-do spirit that we often associate with sports.

But when you’re the person dealing with setback—again and again—it doesn’t feel so great.

It’s hard to exist in a world of sports and fitness with a body that doesn’t always cooperate. I often feel like I’m fighting with my body, that if I just kept pushing it, I would eventually break through to the other side, proving that I can be active and athletic. But more often than not, I just end up breaking down.

My doctor has told me on more than one occasion that I have “loose joints.” Could that be the root of the problem? Even if it is, what can you do about something that’s just part of your physiology?

Maybe my mom was right. Maybe my body wasn’t made for sports.

But when I dig a little deeper, I’ve realized that there’s always been something that made me think that my body and sports weren’t the best match. And it didn’t start with the injuries.

I started playing sports in fourth grade. I transferred to a private school in a more affluent part of Connecticut, where I grew up. Everyone played sports after school—field hockey in the fall and lacrosse in the spring. (I can’t remember what I played during the winter.) It set the stage for sports to be a regular part of my life. In middle school and high school, I ended up playing a variety of sports—soccer, volleyball, swimming, track, some water polo—and skied in the winter with my family.

I wasn’t the best player on the team, but I was decent. Good even. A solid player who was consistent and dependable. Freshman year of high school, L and I were a formidable attacking duo on our soccer team with L at center forward and me at left wing. I’d send the ball over the L; she’d score.

But my contributions were often met with surprise from my coaches and classmates. Not in a mean way but they just didn’t expect me to play well. I was often overlooked or get a lot of praise from my coaches. People always congratulated L on our wins while I cheered her on.

I was one of only a handful of Asian students at my school. Growing up, Asians weren’t really represented in sports in the U.S., aside from figure skating and gymnastics. And sports were antithetical to the ideal of Asian beauty that I grew up with—thin and petite, definitely someone who did not play sports. My mom balked at my active lifestyle and still does. She doesn’t understand why I want to exercise or lift weights, why I like to run, and why I keep pursuing these activities even though I always get hurt.

Even today, the idea that “Asians aren’t athletic” still persists. It’s an unconscious bias that creeps out every once in a while. When my son switched baseball teams a couple of years ago, the coaches gave him a once over. He’s on the smaller side for his age and was probably dressed in random sweats and a t-shirt, not decked out in athletic gear. They explained the drill to him and I could tell from the tone of their voice that they assumed he didn’t have a lot of experience. It’s the same tone that I still get when I walk into a ski shop and they assume that I’m a beginner.

But my kid has played baseball for years. He’s a smart infielder with an innate sense of the game and a good arm. After practice, the coaches came up to me and said excitedly, “He’s a good player!” I nodded and held my tongue at their surprise. I knew they didn’t mean anything by it. And yet.

Am I the Only One?

This idea of having a body that isn’t fit for sports is something that I’ve been thinking a lot about. It’s actually frames many of the questions that I ask in my forthcoming book. And it’s not just about injury.

“As a journalist, I’ve noticed that as women have excelled at sports, there’s an underlying sense that women and their bodies are an anomaly in the athletic world…When something goes wrong—injury, burnout, overtraining—women are blamed and shamed for it, despite doing everything they’re ‘supposed’ to do.”

The stories we tell ourselves, and that others tell about us, matter. I wonder how much of the narrative I’ve been told—and have told myself—about my body and its place in sports has influenced how I move through the world of fitness and athletics. Because the idea that I not an active or athletic person or that I’m injury-prone is always in the back of my mind. Does that create a negative stereotype that make me a magnet for injury?

Last week, I saw my doctor about my knee. As he was leaving the room, I probably said something pooh-poohing my injury. He stopped and turned to me: “You’re out there living your life and doing the things you love. There’s nothing wrong with that.”

What I’m Reading:

This piece from Gloria Liu in Outside, who spent seven hours riding the chairlift at Northstar at Tahoe to find out why people still ski, and this piece from Caleb Daniloff in Runner’s World about how running with his daughter’s dog helped him cope with his daughter’s addiction.

What I’m Listening To:

This podcast with Cheryl Strayed and Liz Tigelaar in which they discuss adapting Strayed’s book TINY BEAUTIFUL THINGS for Hulu but it’s really about more than that—female partnership and vulnerability and creativity. Also this podcast with Erica J. Berry, whose book WOLFISH recently debuted, about writing memoir and finding the through line, and how one’s relationship with writing changes over the years.

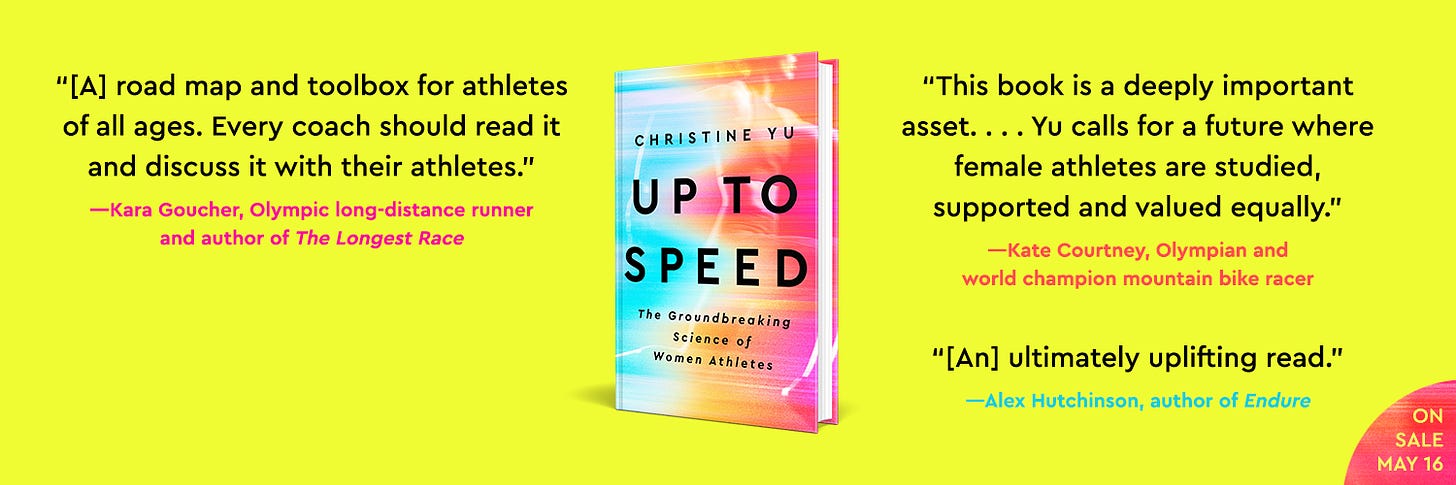

Lastly, it’s 2 months until UP TO SPEED debuts! It’s available for pre-order now—hardcover, e-book, and audiobook! If you want a signed copy, you can order it here.

Thank you for reading. Thank you for being here.

More soon,

Christine

It was about this time last year when you offered me support with my torn ACL & MCL. I’m so sorry to hear about lefty! The commentary on “why are you always injured?” resonates with me. I figure no one gets out of here alive, so I might as well push a little and see what this body is capable of. Wishing you an efficient yet thorough rehab journey.

I love this. I always get asked why I do my sports pursuits (hockey, weightlifting, OCR, power yoga) despite an accumulation of injuries. I mean, not only do I not “need” to work out that much to be “healthy”, it seems counterproductive (and even medical professionals seem to think I should be happy with a few long walks and some 5lb pink dumbbells). I also don’t look like an athlete (50 years old, short, stumpy, no 6-pack to be found), with the implication that I’m not even getting aesthetic benefits.

But..I love it. I love feeling strong and finding new things my body can do. I love the feeling of just just going balls-to-the wall, no fear. I love knowing that it’s ok and often a good thing to be uncomfortable and live with it instead of trying to escape it.

I don’t love contemplating what’s left of my rotator cuff, or every morning cataloging what hurts/is stiff, and more of my training time is now devoted to mobility/range of motion work, but still.

Sitting on my couch, or strolling around with pink weights is unlikely to make me feel physically better and it won’t make my soul, spirit, or psyche feel better. So I just go on, throwing myself at the wall (mountain, clean&jerk, handstand).